I have to state a caveat before I begin. These are not necessarily the top ten, they are the ten that have influenced me in a way that is easily identifiable. It's entirely possible that there are people who have influenced me more than people on this list, but in ways I can't identify or remember as well. Numbers 2-10 are listed roughly chronologically, and I have grouped together people who have influenced me in similar ways.

1: Jesus Christ.

There is a lot I could say here, but the most important thing is that nothing that matters in my life would ever last if it wasn't for what Jesus Christ did. I don't know how something that happened 2,000 years ago can be such a powerful and direct strength to me, but I know that it is. I know that my character and my greatest desires are directly attributable to the power that comes from Christ's atonement.

2. My dad.

Throughout my teenage years, my dad never stopped letting me know the kind of potential he knew I had. He never stopped letting me know that I was capable of more than I was doing. He cared about my success. My response was somewhat of a delayed reaction, but because of his example, I've gained a desire to reach my highest potential. Thanks, dad. I love you.

3. Oliver Sacks.

Oliver Sacks basically gave birth to my love of neuroscience. For those who haven't seen the movie Awakenings, it's about his work with a group of patients suffering from a Parkinson's-like neurological disorder in which they are unresponsive to almost anything. Sacks figures out how to treat their condition, and remarkably many of them "wake up" and are able to live normal lives for a while. Unfortunately, the medication used to treat their condition eventually wears off, and they become unresponsive once again. Oliver Sacks told stories that opened my eyes to how truly amazing the brain is, and it made me hungry to learn more.

4. Carl Sagan.

Carl Sagan makes science an art. His description of the wonder of modern science and the discoveries we've made borders on poetry. Often, science is viewed as an extremely left-brained, analytical, and objective pursuit of life, which it frequently is. But Sagan paints a picture of the beauty and awe inherent in the way the world and the universe and life work. I love science, and I'm going to spend the rest of my life doing it, but anytime it gets too black-and-white, Sagan brings the color flowing back in for me.

5, 6, and 7: Lawrence E. Corbridge, King Benjamin, and James Watson.

These three people set into motion an extended experience that was really what made my LDS mission, and much of my life since then, meaningful for the best reasons. I've summarized this experience in

a previous post, but I'll elaborate a little more here. Lawrence E. Corbridge gave a talk/speech entitled "The Fourth Missionary" that explained the difference between doing the right thing because you're supposed to and doing the right thing because you want to. As a missionary, I had mainly the former attitude at the time I read this talk, but I wanted to do the work out of desire. Corbridge's talk inspired me that such a change was possible, and convinced me that it was something I needed to look for.

I began searching the scriptures for stories of people whose hearts were changed to have desires to do good. The best example I found was in the book of Mosiah in

the Book of Mormon, when an ancient American king teaches his people about experiencing a change of heart by the power of the Holy Ghost. I read his sermon multiple times over the period of a couple months, and James Watson, my missionary companion at the time, was my mentor and example through it all (largely without meaning to be, I'm sure). Nothing happened abruptly, but I know that because these things helped me open myself to the influence of the spirit of God, He changed my heart and helped me have a desire to do good. I owe more to that than almost anything.

8. Don R. Clarke.

In many Christian denominations, services include the observance of the sacrament, also called the Lord's supper. It is reminiscent of

the last supper of Jesus Christ and His apostles, in which Christ gives bread and wine to remind His followers, then and now, of His crucifixion, suffering, and sacrifice for all of us. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, the sacrament is observed each week during Sunday services, and for those like me who have grown up in the church, it's easy to lose appreciation for the ordinance. Elder Clarke helped to bring life back into this experience for me. He gave me specific ideas of what I could do to make the sacrament meaningful each week, ideas that are summarized

here. As I apply his suggestions consistently, the effect has been gradual, but the sacrament has become a source of great spiritual power and strength in my life. It keeps me safe from falling into old habits and helps me keep moving forward. Near the end of my mission, I wanted to make sure there was a way to keep all of the incredibly valuable character developments I experience. Because of Elder Clarke, observing the sacrament helps me to avoid losing any progress I've made. Week after week, year after year, this has become a life-preserving spiritual resource for me.

9 and 10: Eliezer Yudkowsky and Douglas Hofstadter.

I'd be surprised if anyone reading this knows who Eliezer Yudkowsky is. Not only would that require my level of geekiness, it would also require my specific kind of geekiness, and given the readership of this blog, that's simply too improbable. Let me sum up. Eliezer Yudkowsky is the author of an online Harry Potter fanfic called

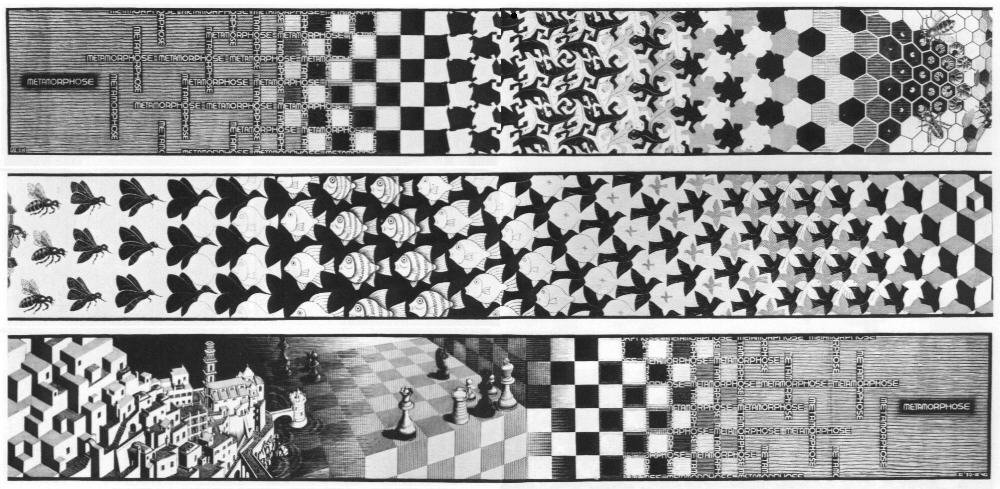

"Harry Potter and the Methods of Rationality" (and yes, I can hear the laughter from here). The Harry in this story is an incredibly intelligent young boy whose intellectual acuity is far beyond those of his peers, much like Ender Wiggin of Ender's Game fame. Like Ender, Harry has a highly developed ability to read people, is extremely creative, and can make intelligent decisions rapidly. Harry makes multiple references to Douglas Hofstadter, including his award-winning book "Godel, Escher, Bach", much of which I have read. Harry uses principles of decision theory, science, mathematics, and probability, as well as his inherent skills, to get himself into and out of a variety of intense and difficult situations.

The story, while its plot is highly engaging, is in many ways a front for Yudkowsky to promote the idea of applied rationality. I could spend a whole post talking about applied rationality, and probably will, but this post is dedicated to how it's influenced me. I consider myself an intellectual by nature, and rationality has made me at least twice as much as I was before. I spend a great deal of in-between time thinking about rationality, intellectual acuity, and how I can multiply my opportunities simply by being smart about the way I make decisions. And I have to admit it's kind of a stimulant for me. I definitely think about it more often than I should, and I definitely use it to compare myself to other people far more than I should. Ways to conscientiously make yourself smarter are inherently addicting, especially for a left-brained person like me. Practicing rationality has taken several of my unique traits and multiplied them, and it's starting to throw things off balance in a way I can't really describe yet. In my current habitat of academia, this imbalance is largely working to my favor, but I need to take some time and consider how it's affecting other necessary areas of my life. Other areas that I'm going to want to take part in someday, even if not right now.